Making A Hole-in-the-Rock

Was The First Step Of A 250 Mile Trek

Hole-in-the-Rock has a history almost as long as the history of the discovery and naming of Glen Canyon by John Wesley Powell in 1869.

The discovery of Glen Canyon was made in the spirit of the exploration of the Colorado River.

The discovery of the Hole-in-the-Rock was made in the spirit of the expansion of the territory occupied by the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

In 1878 and 1879, a call went out from the Mormon Church in Salt Lake City seeking families willing to relocate to that part of the country east of the Colorado River along the San Juan River.

In April, 1879, Silas S. Smith led a scouting party to look for a suitable location for a new colony.

They were successful in finding a place near the mouth of Montezuma Creek on the San Juan River.

The only problem with this location was that it was almost 500 miles away if they were to use either of the routes used by the scouts.

They needed a short-cut.

Later that year they were successful in finding one, and on October 22, 1879, families from Cedar City, Parowan and Paragonah began the trek to Escalante, Utah.

1 Escalante Desert 2 Escalante River 3 Kaiparowits Plateau 4 Dance Hall/40 Mile 5 Fifty Mile Spring 6 Hole-in-the-Rock 7 Cottonwood Canyon 8 Cottonwood Hill 9 The Chute 10 Gray Mesa 11 Slick Rocks 12 Death Valley 13 Lake Canyon 14 Castle Wash 15 Clay Hills 16 Dripping Spring 17 Grand Gulch 18 The Cedars 19 Salvation Knoll 20 Owl Creek 21 The Twist 22 Comb Wash 23 San Juan Hill 24 Bluff

|

The wagons were loaded with all of their personal goods and tied to the sides of the wagons were water barrels, cages of ducks, chickens, rabbits and even bee hives. Everything they thought they would need in Montezuma. |

Books and Maps about The Hole-in-the-Rock may be purchased through Amazon.com by clicking the link below.

|

In November of 1879 the San Juan expedition, as it was then known, gathered at Forty-Mile Spring, south of the village of Escalante, Utah.

The expedition consisted of eighty-three wagons, 250 men, women and children, and over 1,000 head of stock.

Little did they know at the time, the herculean and almost impossible task they were undertaking:

• It was winter, and heavy snow already blanketed the ground covering any grass forage for the stock and obscuring the trail back to Escalante.

• Hole-in-the-Rock was nothing more than a narrow slit in the canyon wall and would have to be widened to allow passage of the wagons.

• Huge rocks and boulders filled this narrow chasm to the river and would have to be cleared.

• It was approximately 2000 feet to the Colorado River below.

• Their only tools were pick axes, shovels, chisels and a limited amount of blasting powder.

• The gradient was steep, with an average of 25 degrees, but sometimes as steep as 45 degrees.

• When they reached the river, they would have to build a ferry to cross it.

• Once across the Colorado, they still faced 150 miles of rugged, almost impassable terrain.

• Food and other necessities were in short supply.

Is it any wonder that many of those in this expedition thought this was “Mission Impossible,” and wanted to turn back?

And, if they had who would have blamed them if they did?

And so it came to pass that while they were camped at Forty-Mile Spring, Silas S. Smith, the head of the expedition, met with some of the leaders to discuss their options: go back, remain where they were or continue ahead.

After a great deal of discussion, the group decided to leave the decision to Smith and the Lord.

The following morning, Smith announced to the group that they would continue with their expedition.

Remarkably this announcement was received with a great deal of enthusiasm, and the expedition set out for Fifty-Mile Spring where they would establish a temporary camp.

|

|

|

|

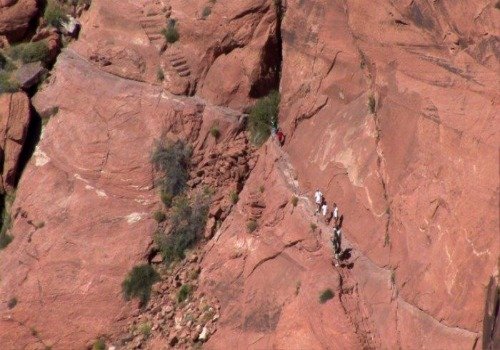

Rim at the Top of Hole-in-the-Rock |

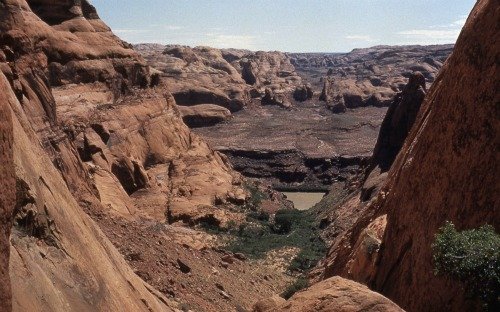

Hole-in-the-Rock Before Lake Powell |

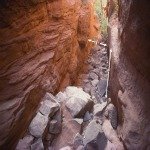

First Corridor of Hole-in-the-Rock |

At Fifty-Mile Spring, the members of the expedition were split up into three groups:

• One group was to work at enlarging the opening at the top of the rim.

• The second group was to clear the crevice to the river.

• The third group was to build the ferry that would transport the expedition across the Colorado River and would also work on the road beyond the river.

Group one, charged with enlarging the opening at the top of the rim, set to work with pickaxes, chisels, shovels and blasting powder.

Men were lowered by rope, in half-barrels, over the edge of the 45 foot cliff.

Then, dangling from the rope, they would drill holes in the face of the cliff, fill them with blasting powder, return to the top, light the fuse, clear the debris from the blast and do it again.

While they only had a limited amount of blasting powder,they used it prudently and judiciously, and, in areas of sandstone, they used Mother Nature to break up the stone.

They would drill holes or use existing cracks, fill these holes and cracks with water, let the water freeze and expand, thereby breaking off slabs of rock,slowly and surely ever-widening the crevice

|

|

|

|

Lines Showing Pathway Of First Drop |

Looking Up From First Drop |

Drilled Holes of Uncle Ben's Dugway |

Group two, charged with making a pathway to the river, also relied on skill and ingenuity.

Along a shear canyon wall, they chiseled a narrow path out of the canyon wall which would support the inside wagon wheels.

Then, about five feet below this ledge, and parallel to it, they drilled ten inch holes, about 21/2 inches in diameter and about 18 inches apart.

Into these holes they pounded cedar stakes, cut and hauled from the Kaiparowits Plateau above them.

Between the wall and the stakes, they laid down logs, then rocks, brush and finally gravel, until they had a nice pathway wide enough for a wagon; the inside wheels supported by the wall ledge and the outside wheels supported by the raised platform.

They called this “Uncle Ben’s Dugway” in honor of its designer Benjamin Perkins.

Uncle Ben's Dugway Near Bottom of Crevice

Lower Section of Crevice & Colorado River

Group three’s task was equally as challenging as groups one and two.

In fact, it may have been the most challenging of the three, because not only were they asked to build a ferry to carry everyone and everything across the Colorado River, but they were also asked to build a road up a 250 foot rock incline from the river to Cottonwood Canyon.

As there were no suitable trees available nearby, timber for the ferry had to be hauled all the way from Escalante.

Once at the site, it was fashioned into a ferry capable of carrying two wagons. Two wooden oars were fitted to the ferry and would provide the locomotion for crossing the river.

Finally, on January 26, 1880 the three groups had completed their work and the expedition was ready to start down the crevice to the river below.

That is, the men, women and children were ready but the horses were not.

Whenever a team of horses pulling a wagon was brought to the rim of the chute, the horses saw the river 2000 feet below, and balked and would go no further.

After three unsuccessful attempts to get horses and wagons started down the crevice, one of the members brought his horses to the rim.

They had been blind for more than a year because of a pink eye epidemic which had blinded them and several hundred other horses in southern Utah.

Without hesitation, but carefully and with exceeding caution, these horses felt their way down the crevice and to the awaiting ferry.

With this team of blind horses leading the way, the others were apparently reassured and followed in their footsteps.

Because of the steepness of the crevice, each of the wagons had its rear wheels locked, the brake set, and a rope attached to the rear of the wagon and handled by a team of ten men or so who struggled to keep the wagon from becoming a run-away.

|

|

|

|

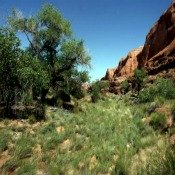

Vegetation At Cottonwood Canyon |

Cottonwood Canyon Original Pioneer Trail |

Dugway Cottonwood Canyon |

By the end of the day, 26 wagons had made it down the crevice and across the Colorado River, and by the end of January all of the wagons were now camped east of the Colorado River at an area which became known as Cottonwood Canyon Camp.

Here they would remain for ten days while work continued on the road out of the canyon.

At last, on February 10, 1880, the expedition was once again on its way eastward.

But first they had to get the wagons up the steep and treacherous Cottonwood Canyon Hill, an incline so steep that it took seven teams of horses to haul each wagon to the top.

And so it would continue for another two months and another 150 miles of rough, inhospitable and untamed country.

Amazingly, not a single life was lost. In fact, two babies were born along the way.

Finally, on April 6, 1880, the expedition came to an area with good farmland along the San Juan River.

This was twenty miles short of their destination of Montezuma, Utah, but they were too tired, weary and exhausted to continue further.

They named this place Bluff City, later shortened to Bluff.

The Hole-in-the-Rock shortcut continued to be used for another year.

Charles Hall and his two sons, who were part of the third group which had built the ferry, continued to operate it until 1881 when they found an easier crossing about 35 miles upstream.

The Halls then operated their ferry at this new location until 1884 when their ferry was either intentionally cut loose by cattlemen to prevent its use by rustlers or by an act of God.

The Halls never replaced the ferry and left the area soon after. Hall’s Marina now occupies this site.

As a side note to this story, the Mormon Handcart Pioneers, who pushed and pulled handcarts from Iowa City, Iowa to Salt Lake City, Utah made their trip of approximately 1,300 miles in about two and one-half months.

The Hole-in-the-Rock Expedition, as it became known, took six months to make their way to Bluff City, Utah; a trip of approximately 200 miles.

Although I relied heavily on the articles by Larene Porter Hunt and O. Ned Eddins, which I have referenced below, I owe a deep debt of gratitude to Lamont Crabtree of the Hole-in-the-Rock Foundation at Bluff, Utah.

He was most kind in allowing me to use some of his high resolution photographs which so strikingly portray the Hole-in-the-Rock passage.

All photos and map are Courtesy Lamont Crabtree.

I encourage anyone interested in this epic and courageous journey to visit the links below.

Directions to the Hole-in-the-Rock:

By Boat:

Hole-in-the-Rock is 66 miles up-lake from Glen Canyon Dam. Look for buoy 66.

If you are heading down-lake from either Bullfrog or Hall’s Crossing Marina, it is approximately 30 miles.

By Motor Vehicle:

Hole-in-the-Rock road is approximately 5 miles east of the town of Escalante, Utah off State Road 12.

This is a dirt road and not recommended for two-wheel drive vehicles.

Even four-wheel drive vehicles can have trouble after heavy rains.

From the turnoff, it is 62 miles to the rim.

Have A Great Story To Share?

Do you have a great story about this destination? Share it!

References:

Hole-in-the-Rock Foundation

P.O. Box 476

Bluff, Utah 84512

http://www.hirf.org

inquiry@hirf.org

Larene Porter Gaunt, Associate Editor, “Hole-in-the-Rock”

The Ensign of the Church of Jesus Christ

of the Latter-day Saints

(October, 1995)

http://www.lds.org/ensign/1995/10/hole-in-the-rock?lang=eng

O. Ned Eddins, “Hole-in-the-Rock Expedition”

http://www.thefurtrapper.com