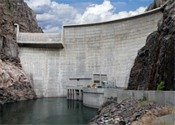

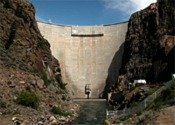

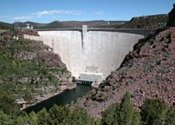

Glen Canyon Dam And Its Reservoir: Lake Powell

Glen Canyon Dam

Photo: Wikimedia Commons - Agunther

Glen Canyon Dam, located on the Colorado River near the northwestern Arizona town of Page, was built to provide:

• Water storage

• Flood control

• The reclamation of arid and semi-arid lands

• Clean hydroelectric power

• Recreational opportunities for millions of visitors.

Although it is the second largest dam on the Colorado River, behind Hoover Dam in Nevada, its reservoir, Lake Powell, is 186 miles long and has almost 2 ,000 miles of shoreline.

In comparison, Hoover’s, Lake Mead, is 110 miles long and has only 550 miles of shoreline.

Quick Facts:

• Construction Started: October 15, 1956

• Last bucket of concrete poured: September 13, 1963

• Water began filling Lake Powell: March 13, 1963

• First hydroelectric power generated: September 4th, 1964

• Glen Canyon Dam officially opened: 1966.

• Completion of initial filling: June 22, 1980

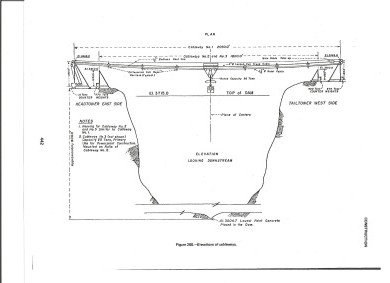

• Type: Concrete Arch

• Height: 710 feet

• Crest length: 1,560 feet

• Thickness at Crest: 25 feet

• Base Thickness: 300 feet

• Amount of Concrete poured for dam: 4,901,000 cubic yards

• Amount of Concrete poured for power plant: 469,000 cubic yards

• Total amount of concrete poured: 5,370,000 cubic yards

• Capacity of concrete bucket: 24 tons

For those of you who are interested only in the quick facts and really don’t care about the history and construction of the dam, this would be a good stopping point.

You may, however, find interesting the controversy surrounding the dam, and, if so, please see my page on Glen Canyon Dam Controversy.

Also, I think you will enjoy reading about the Carl Hayden Visitor Center which sits high atop the dam like the captain’s cabin aboard a modern ocean liner. If so, please Click Here.

History:

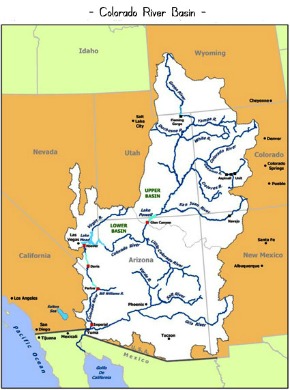

The arid southwest, as the name implies, is a dry land with little annual rainfall. Water has always been a valuable but scarce commodity, one over which feuds have been waged and lawsuits filed.

For many years, the Colorado River, and her many tributaries, have been an important source of water for this dry and thirsty country.

In the late 19th century and early 20th century, as more and more people moved to the west and southwest, the demand for water increased. However, there was only so much water available.

As a result, all of the states through which the Colorado River flowed fought for the right to take water from the river.

In 1922, representatives from Arizona, California, Colorado, Nevada, New Mexico, Utah and Wyoming met at Bishop’s Lodge near Santa Fe, New Mexico and signed the Colorado River Compact.

It allocated the amount of water each state was allowed to take from the river. Congress ratified this Compact the same year.

|

However, one of the problems with this compact was the fact that rainfall and snow melt vary from year to year. Thus, it was not always possible to retain enough water to meet the needs of the states in the upper basin and, at the same time, to deliver the specified amount of water to the lower basin. Reclamation's answer to the problem was to build dams along the Colorado River and some of her tributaries. |

Books about Glen Glen Canyon Dam |

Not only would they provide the means by which to store water but they would provide clean hydroelectric power, recreational opportunities in the reservoirs behind them and prevent floods.

|

|

|

|

Blue Mesa Dam Photo: USBR |

Crystal Dam Photo: USBR |

Morrow Point Dam Photo: USBR |

In 1950, the Bureau of Reclamation presented to Congress a plan to build a number of dams.

In this plan, they proposed five projects, to be completed in two phases. In the first phase were:

• Flaming Gorge – on the Green River near Green River, Wyoming

• Curecanti – 3 dams along the Gunnison River in Colorado

• Martinez (later called Navajo) - on the San Juan in New Mexico

• Glen Canyon - on the Colorado River in Arizona

• Echo Park - near the confluence of the Green River and the Yampa River in Utah

In the second phase, they proposed building a dam in the Split Mountain Gorge which is downstream from Echo Park and whose waters would back up into Whirlpool Canyon, named by John Wesley Powell “… on account of many whirlpools existing at that stage of water…”

Echo Park and Split Mountain Gorge are both located within the Dinosaur National Monument, and when word got out that Reclamation wanted to build two dams within the monument a fire storm of protest was ignited.

It is well known and well documented that David Brower, Director of the Sierra Club, and Olas J. Murie and Howard Zahniser of the Wilderness Society waged a nationwide protest to the building of these dams.

To see a 3 minute video about the fight to save Echo Canyon in Dinosaur National Park, please Click Here.

This will open a page in Richard's Scrapbook.

Once there, click the video to begin.

However, there were others who fought just as hard and just as long. One of these was Dr. Harold Bradley, a retired chemistry professor from the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

In 1952 he and his family spent a week rafting the Yampa River in Colorado. They took photographs and recorded their trip with a movie camera which they began showing to various groups and organizations in opposition to the Echo Park Dam.

He encouraged the Garden Club of America to mail leaflets to members urging them to write their congressmen about it.

Other organizations like the General Federation of Women's Clubs and the National Wildlife Federation became involved in this campaign.

Alfred A. Knopf, a New York City publisher, rafted the Yampa River and was so impressed that he commissioned a book of essays and photographs. The result was: This Is Dinosaur: Echo Park Country And It’s Magic Rivers, edited by Wallace Stegner with photographs by Philip Hyde and Martin Litton.

And so the battle continued with more and more pressure being put upon the members of congress to remove Echo Park from the CRSP.

|

|

|

|

Flaming Gorge Dam Photo: USBR |

Glen Canyon Dam Photo: Wikimedia Commons |

Navajo Dam Photo: USBR |

Finally in November of 1955, Secretary of the Interior, Douglas McKay, announced that the Echo Park dam had been removed, and on April 11, 1956 the U.S. Congress authorized “… the Secretary of the Interior to construct, operate and maintain the following initial units of the Colorado River storage project….”

• Curecanti (Later named Aspinal in 1980 For US Representative Wayne Aspinal

- Crystal Dam

- Morrow Point Dam

• Flaming Gorge Dam

• Navajo Dam

• Glen Canyon Dam

Requests for Proposal (RFP) quickly went out for the construction of Glen Canyon Dam.

It was such a daunting job that only three companies responded to the RFP.

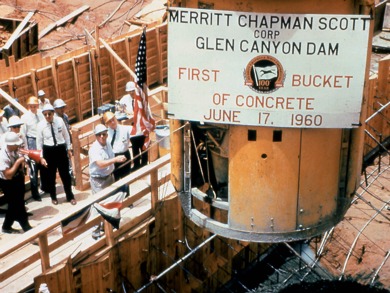

The construction firm of Merritt-Chapman Scott was the low bidder at just under 108-million dollars, a bid that was even lower than Reclamation anticipated.

Lem F. Wylie was appointed chief construction engineer for the Bureau of Reclamation and he faced a monumental task.

Not only did he have to build the dam, but he had to:

• Build a town to house an estimated 2,500 Dam workers and their families

• Extend State Road 89 which ended at Bitter Springs, north of Flagstaff, Arizona and add 56 miles of road from Kanab in southern Utah to the Dam site

• Build a bridge across the Colorado River at the Dam site to connect the two new roads

• Build roads, sidewalks, schools, churches and places of business in the new town-site

• Provide water, electricity and sewage

• Bring in doctors, pharmacies, clothing stores, grocery stores, banks, post office, etc.

Reclamation initially had planned to use Kanab, Utah as their base as it was the nearest town of any size with an infrastructure to support a construction crew.

They leased room in the Kanab High School for “… offices and drafting rooms where fifty men would work on projects related to the dam….”

Reclamation hired contractors to grade two roads to the dam site:

• one road from Kanab, Utah

• one road from Bitter Springs, Arizona

Although these dirt roads were eventually paved, it became apparent that the use of Kanab as a base of operations was not practical; it was just too far from the dam site.

|

|

|

Glen Canyon Before Dam Photo: USBR |

Soils Lab, Field Engineer's Office Photo: USBR |

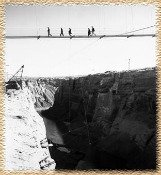

Initially, the construction workers on the dam lived in trailers on the west side of the river.

In order to get workers from the west side to the east side, a seven foot wide footbridge was built across the 1280 foot span from tower to tower.

The footbridge consisted of a wire mesh deck laid on cables stretched across the canyon.

It was built in 60 days and, at the time, was the longest footbridge in the United States.

|

|

|

Footbridge Photo: USBR |

Footbridge Photo: USBR |

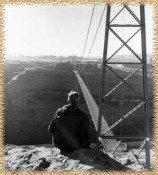

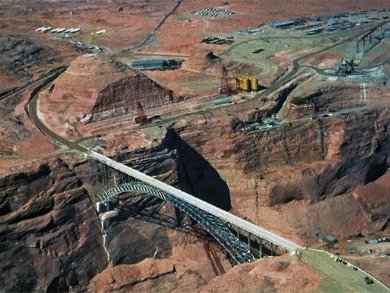

In the meantime, work was going on by the Kiewit-Judson Pacific Murphy Company in California of building a permanent steel arch bridge.

Once it had been constructed, it was to be disassembled, and the sections were to be trucked to the site, half on the east side and half on the west side.

In early May of 1957 the work began of placing and joining the sections on the east side.

In late May they began working on the west side, extending the bridge section by section.

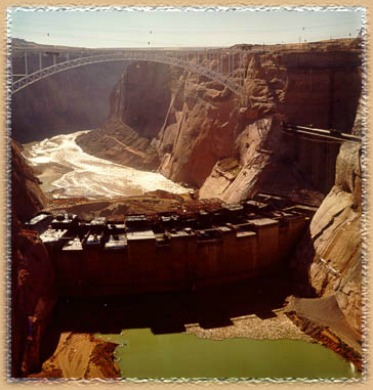

The bridge was completed on August 11, 1957 and at 1,271 feet long and 700 feet above the river was the highest bridge of its kind in the United States.

It was dedicated on February 20, 1959.

Glen Canyon Bridge During Construction 1959

Photo: USBR

Town-Site

Now that a bridge had been built across the Colorado River, and there was a continuous road linking Flagstaff, Arizona and Kanab, Utah, it was time to concentrate on a place for the dam workers to live.

On March 22, 1957 the Bureau of Reclamation exchanged a piece of land in southeastern Utah, known as McCracken Mesa, for 24.3 acres of land located just a few miles southwest of the dam site.

This land was owned by the Navajo Nation and was occupied by the Manson Yazzie family under the Navajo Tribal grazing program and was known as Manson Mesa.

As it turned out, this was one of the few times when the Native Americans got the better of the white man: McCracken Mesa is now part of the rich Aneth Oil Fields.

|

|

|

Future Site Of Page, AZ Photo: USBR |

Government Camp Photo: USBR |

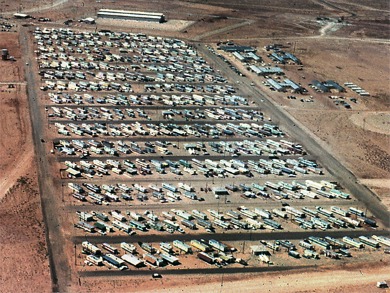

The Bureau began to lay out the streets for the town and brought in trailers to house the workers and temporary metal structures for schools, laundromats, businesses and professional offices.

Babbit Brother’s Trading Post was the first grocery store and the largest metal building in this new government camp.

Aerial view of trailer park housing for workers - 1958

Photo: USBR

Government Camp was later named Page after John C. Page, who served as Commissioner of the Bureau of Reclamation from 1937-1943 and was an advocate of reclamation projects in the western United States.

Page was a federal municipality until March 1, 1975 when it became incorporated.

Diversion Tunnels:

Before any work could be done on the dam itself, it was necessary to divert the flow of the Colorado River.

This was to be done by building two tunnels, one on each side of the river.

Each tunnel was to be 2,700 feet long and 41 feet in diameter.

|

|

|

Initial Spillway Construction Glen Canyon Dam Photo: USBR |

Progress of Spillway Construction Glen Canyon Dam Photo: USBR |

The tunnel on the right would be used to handle the normal flow of the water around the dam site, and the one on the left, 33 feet above the water, would be kept in reserve to be used, along with the right tunnel, to handle floods.

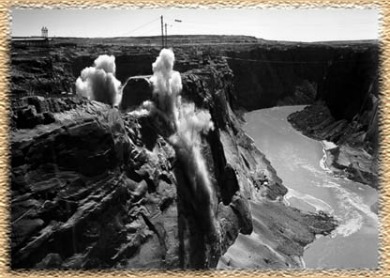

On October 15, 1956, six months after Congress authorized the dam, President Dwight D. Eisenhower, from the Whitehouse in Washington, DC, depressed a telegraph key that ignited the first explosion at the dam site displacing large amounts of sandstone rock from above the right diversion tunnel.

Blasting At Glen Canyon Dam

Photo: USBR

With this explosion, construction of the second largest dam on the Colorado River had begun, but, as momentous as it was, this was only the first of many such explosions.

The sandstone rock that formed the canyon wall was, by its very nature, subject to flaking and giving way to gravity.

During the excavation of the tunnels and the widening of the dam site, the rock would often flake off in huge slabs and come crashing down.

To stabilize the rock, hundreds of holes, up to 72 feet deep, were drilled into the walls and ceilings and long metal bolts with expansion anchors were inserted. Concrete was then forced into the area around the bolts, thus securing them to the wall.

As the tunnels grew in length, width and depth all of the material that had been excavated had to go somewhere.

That somewhere was into cofferdams built ahead of the dam site to hold back the Colorado River, then once the tunnels were completed, to divert the water into the right diversion tunnel.

On February 11, 1959, a little over two years from the initial blast, the Colorado River was released and began flowing into the right diversion tunnel.

Three months later, the left diversion tunnel was completed.

Glen Canyon Dam

With the diversion tunnels now complete and the Colorado River flowing freely through the right tunnel, construction could now begin on the physical structure of the dam itself.

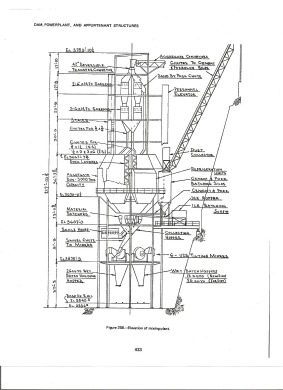

Batch/Mixing Plant

Photo: USBR

A concrete mixing plant was built near the dam site.

It was a huge structure, over 217 feet, equivalent to a 20-story building, and mixed the material for the concrete at the rate of 1,450 tons an hour.

According to George C. Bailey in Cooling for Dams, published in March 2004 in ASHRAE Journal:

“When concrete is used in massive structures, such as dams, foundations, and some concrete highways, it must be cooled to minimize cracking.

Refrigeration is required to offset the heat of hydration of cement after pouring.

Cooling causes concrete to shrink while the mass is still in a semifluid state, which reduces the possibility of cracking.”

|

The concrete mixture coming out of the batch plant before refrigeration was about 95 degrees Fahrenheit. Per specifications, it had to be 50 degrees Fahrenheit. Therefore, the temperature had to be reduced 45 degrees. This was accomplished in four steps: |

• Spraying the aggregates with water cooled to 35 degrees as they moved along a conveyer belt to the batch plant

• Air cooling the aggregates while in bins at the batch plant

• Chilling the mix water to 35 degrees

• Adding flake ice to the mix

These four processes actually reduced the mixture to 47 degrees, 3 degrees below the required 50 degrees, but it provided insurance that the mixture would be 50 degrees by the time it was poured into the forms.

Additional cooling of the concrete after it was placed was accomplished by circulating cold water through 1” aluminum pipes embedded in the base of each form.

This was done in two stages.

In the first stage the water was chilled from 38 to 47 degrees for a period of 12 days.

The second stage called for the water to be chilled to 38 degrees.

Water was later switched to brine which was chilled from 35 to 28 degrees in the final stages. This second stage was for a period of 52 days.

Cable Ways

In order to deliver the cement from the batch/mixing plant to the concrete forms of the dam two 50-ton-capacity mobile cableway systems had to be designed and erected.

The design was made by Lidgerwood Industries.

Cable Ways and Towers

It called for two mobile towers on each side of the canyon.

Each of the towers was set on four 8-wheeled trucks, one under each leg of the tower.

The trucks ran on tracks of 150-pound rails.

On the west side of the canyon, the high tower was 180’ tall and the lower tower was 125’ tall.

Both towers had a lateral movement of 910’.

Due to a difference in elevations of the two canyon sides, the high tower on the east side of the canyon was 130’ and the lower tower was 85’ high.

Both towers had a lateral movement of 810’.

The towers on the west side were referred to as head towers and the ones on the east side were referred to as tail towers.

The total span of the high tower was 2,050’ and the span of the low tower was 1,800’.

The 4-inch cables between the east and west towers were the largest ever used in dam construction.

Approximately every nine to ten months, these cables had to be replaced due wear and tear.

Cement Placement

The first thing that had to be built was the dam’s foundation.

This was done by digging down 137’ to bedrock.

Then wooden forms, seven and a half feet high and up to 60 feet wide and 210 feet long, reinforced by steel rods, were placed along the bedrock

Photo: USBR

On June 17, 1960, Secretary of the Interior, Fred A. Seaton, in a ceremony attended by various dignitaries, including the governors of Arizona, Colorado and Utah, pulled a cable dumping the first 12-cubic bucket of cement into the forms.

After the concrete blocks were cured, the wooden scaffolding was removed and moved up to the next tier.

As the work progressed and the dam grew higher, the wooden forms were replaced by steel forms.

Glen Canyon Dam emerged from bedrock incrementally, as a series of blocks seven and a half feet high until it reached a full height of 710 feet.

Glen Canyon Dam in 1962

Photo: USBR

Work on constructing the dam continued 24 hours a day until on September 13, 1963, the last of over 400,000 buckets of concrete was placed.

The dam itself was completed in 1963 and over the next three years the generators and turbines were installed.

On September 22, 1966, Lady Bird Johnson dedicated Glen Canyon Dam.

Glen Canyon Dam Dedication

Photoe: USBR

This has been a very brief synopsis of Glen Canyon Dam, although some may argue that I have gone into more detail than really necessary.

I would be remiss, however, if I failed to bring your attention to the controversy that has been so much a part of its history, even before President Dwight Eisenhower ignited the first charge in 1956.

Unfortunately, over 50 years later, the controversy still wages.

If you are interested in learning more about this interesting and highly emotional topic, please see Glen Canyon Dam Controversy.

For anyone truly interested in the construction of Glen Canyon Dam, I highly recommend Technical Record of Design and Construction, Glen Canyon Dam and Powerplant prepared by the Bureau of Reclamation.

To Drain or Not to Drain?

That is the Question!

Even before construction on Glen Canyon Dam began, it was steeped in controversy.

There were many opponents who felt the dam should not be built and their passions ran deep.

They pointed to the pristine wilderness of Glen Canyon and bemoaned the loss of such magical places as Music Temple, Cathedral in the Desert and Outlaw Cave.

But, just as passionate were those proponents who felt that building the dam more than justified these losses.

They talked about hydroelectric power, taming the Colorado River and providing much needed water to thirsty lands.

And, now that the dam has been built, and each side has seen their predictions come true, there is talk about draining the lake and returning it to its natural state.

My question to you is: Should Lake Powell be drained?

I would like more than just Yes or No.

I want to know why you feel the way you do;

maybe some personal experience that has shaped your conviction, pro or con.

Also, I would love to see and share your photos.

References and Resources:

Technical Record of Design and Construction

Glen Canyon Dam and Powerplant

prepared by the Bureau of Reclamation.

http://www.gcmrc.gov/library/reports/other/Power/BureauOfRec1970.pdf

Upper Colorado Region

Colorado River Storage Project

Glen Canyon Dam Construction History

http://www.usbr.gov/uc/rm/crsp/gc/history.html

Arizona State University

Nature, Culture, and History at the Grand Canyon

http://grandcanyonhistory.clas.asu.edu

/sites_adjacentlands_glencanyondam.html

An Eminent Engineer Considers Dinosaur

They Need Water – They Don’t Need Dinosaur Dams

U. S. Grant, 3rd

http://www.columbia.edu/cu/lweb/digital/collections/rbml/lehman/pdfs/0436/ldpd_leh_0436_0081.pdf

Colorado River Storage Project-

Authority to Construct, Operate and Maintain

Chapter 203 – Public Law 485

http://www.usbr.gov/lc/region/pao/pdfiles/crspuc.pdf

Glen Canyon

A Dam, Water and the West

http://www.kued.org/productions/glencanyon/reclamation/fieldoffice.html

Glen Canyon Dam

U.S. Bureau of Reclamation

http://www.usbr.gov/projects

/Facility.jsp?fac_Name=Glen+Canyon+Dam

Desert Magazine

July 1956

Boat Trip in the Canyon of Ledore

By Randall Henderson

http://www.scribd.com/doc/2403152/195607-Desert-Magazine-1956-July

Public Broadcasting Service

The Parks vs. the Most Dangerous Animal

http://www.pbs.org/nationalparks/history/ep6/2/

Canyon Country Zephyr

The History of Glen Canyon Dam

http://www.canyoncountryzephyr.com/oldzephyr/feb-march2002/rich.htm

ASHRAE Journal

March 2004

Cooling for Dams

By George C. Briley

www.ashrae.org/File%20Library/docLib/.../200422494219_326.pdf

Wikimedia Commons

Colorado River Storage Project

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Colorado_River_Storage_Project